David's Blog

Snakes and Ladders: Making Ecological Sense of Liberal Democracy

A Multi-dimensional Game of Snakes and Ladders

There is a contradiction at the heart of liberal democracy: while democracy requires social equality, the engine of capitalism creates both wealth and inequality. While direct democracy – the purest form – thrives only in small-scale, face-to-face communities, the interaction of capitalism and technology systematically produces large-scale enterprises and institutions, where people are separated in space and time. Coordination now takes rules and hierarchy, which, together with the accumulation of wealth, leads to the emergence of elites. Over time the interests of these elites will turn to rent-seeking and value extraction at the expense of value creation. Many will strive to retain power by blocking all efforts at its redistribution.

Add to this behavior of the elites the ‘creative destruction’ of technological change and the result is that the relationship between democracy and capitalism changes constantly as technology both creates and destroys, value creation morphs into value extraction and elites accumulate wealth and power. Social inequality grows. The constant dilemma for proponents of liberal democracy is how to harness the productive power of capitalism, while ensuring that its benefits are spread widely enough to maintain a sense of political participation and shared citizenship. It’s a bit like trying to design and manage a multi-dimensional game of snakes and ladders.

Addressing this tension, between democratic responsiveness and institutional stability, was the primary concern of the framers of the U.S. Constitution. They knew, as modern Americans are rediscovering, that when this effort succeeds the result is a resilient society and a robust middle class with a shared narrative of who they are. When the process fails the middle-class fragments and societies become unstable. Oligopolies flourish and elites become entrenched, while many members of the erstwhile middle-class join the ‘invisible class’, losing their stories and their identities: for them the game seems to become all snakes and no ladders. They will then turn to populist politicians and anyone else who promises to restore their lost narratives.

To continue reading this article go to Medium: Snakes and Ladders

Making Sense of Management: Theory and Practice

Plato and Aristotle in detail from Raphael’s School of Athens (1511). Plato points upward toward universal truths and his Theory of Forms, while his student Aristotle indicates that true reality lies lower in the particulars of practice and experience

What’s the relationship between management theory and management practice? Today I published a 3,000-word essay on the topic on Medium. Here’s a brief introduction:

The relationship between theory and practice has vexed management academics and practitioners alike for decades. Traditionally the Anglo-American approach has been to address it as a knowledge transfer problem. This approach was helped by making no distinction between the natural and human sciences. The assumption was that reality was ‘out there’ to be studied objectively and that the goal of knowledge, via the scientific method, was to learn more and more about its true nature. This perspective assigns a superior position to formal-technical ‘scientific’ knowledge and sees practical knowledge as an inferior derivative of it. This was a triumph for Plato’s views over those of Aristotle. Plato had contended that the knowledge of forms or universals was sufficient to understand reality. Aristotle, on the other hand, had argued that, while knowledge of forms was necessary, it was not sufficient: one also needed experience with particulars. He said that this explained why experienced practitioners with little theoretical knowledge often performed better than those who knew a lot of theory but had little experience.

Ever since the Enlightenment Plato’s ideas have dominated Anglo-American management thought but in recent years Aristotle’s views have been making a comeback. Management theory and management practice are increasingly seen as different types of knowledge, with different philosophical assumptions about reality and how we apprehend it. Theory and practice may appear to be in opposition and even as substitutes for each other, but their relationship is best seen as complementary. This complementary relationship becomes clear if one takes a sensemaking perspective which is where my Medium article begins….

Restoring Humanity to Management: the Power of Context

My blog on this topic has just been published on the Drucker Forum here.

My biggest beef with mainstream Anglo-American management (‘Cartesian’ management, as I call it) is that it ignores context. It treats management as an amoral, technical practice, modelled on the natural sciences and often based on what John Dewey called the spectator theory of knowledge. This myth, that we are passive observers who can view the world objectively, lies at the root of our impoverished models of what it means to be human.

Cartesian management sanctions the stripping of apparently successful methodologies from the human contexts that made them successful and presenting them as abstract, context-free ‘principles’ that can be ‘applied’ by anybody in any situation. This disregards the importance of initial conditions and path-dependent nature of whatever happens in practice and perpetuates an illusion of rationality, predictability and control. Many academics and consultants like this approach, but it is anathema to effective managers.

Effective managers know that abstract principles cannot be applied to humans in the same way that they are in the natural sciences. If people are treated as objects – assets and resources – they respond badly. The best management frameworks are those that help managers make sense of the contexts that they are in. The frames direct their attentions and guide their conversations in their search for affordances, the action possibilities afforded by the particular situations in which they find themselves.

It is the ability of managers (a practical wisdom developed through experience) to find these affordances that makes or breaks their efforts. Context matters! This may be why many managers prefer to read history, biography and even fiction to management books. The former offer quasi-experiences that illustrate how other humans discovered action possibilities in the situations in which they found themselves.

Management academics and consultants persist with the Cartesian approach for at least two major reasons. Apart from allowing them to wrap themselves in the mantle of ‘science’, ignoring context broadens the markets and industries that they can address – one size fits all! The second advantage is that the Cartesian approach leaves the current power structure of the organization (and society) unchallenged. This allows a servants-of-power approach, especially in the business schools: “In other words, they say given your ends, whatever they may be, the study of administration will help you to achieve them. We offer you tools. Into the foundations of your choices we shall not inquire, for that would make us moralists rather than scientists.” Philip Selznick Leadership in Administration P 80.

Once again, this is anathema to effective managers trying to enable significant organizational change. They know that power structures that perpetuate the status quo and allow only incremental efficiency innovations are barriers to more radical experimentation. This does not imply a need for wholesale revolution, only continual renewal, as power is spread more widely and moves around the organization. This allows people to exercise responsibility and take action in the areas where they are best suited to do so.

Management cannot be treated as an amoral technical practice that deals only with means and leaves ends unaddressed. Rather, it is also a human inquiry, a moral practice that questions chosen ends and their good for both business and society. People are ends-in-themselves.

The Scientific and the Humanistic Modes of Inquiry

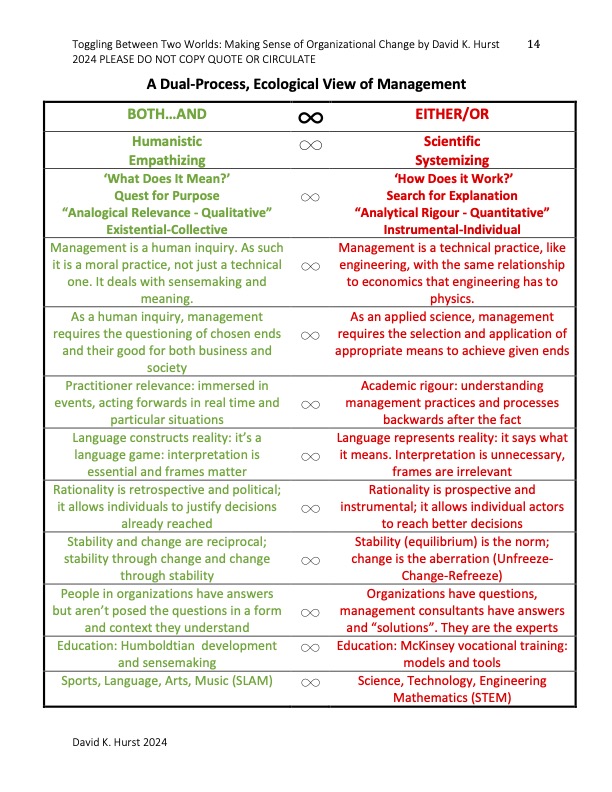

The core of the blog is the diagram, which captures some of my intellectual journey over the last forty years, as I tried to make sense of a major organizational transformation experience:

The contrast between the scientific and humanistic modes of inquiry has many precedents. Among my inspirations were the writings of psychologist Jerome Bruner, psychiatrist/philosopher Iain McGilchrist and many dual process theorists of cognition and emotion. Underpinning it all is the taijitu, the yin-yang symbol of complementary yet opposing forces that form a self-perpetuating cycle of the kinds found in complex ecosystems like forests and estuaries.

The contrast between the scientific and humanistic modes of inquiry has many precedents. Among my inspirations were the writings of psychologist Jerome Bruner, psychiatrist/philosopher Iain McGilchrist and many dual process theorists of cognition and emotion. Underpinning it all is the taijitu, the yin-yang symbol of complementary yet opposing forces that form a self-perpetuating cycle of the kinds found in complex ecosystems like forests and estuaries.

The “Cartesian Search for Truth” and the “Goethean Quest for Meaning” titles were inspired by the long debate on multiple topics between Anglo-American and Continental philosophers, particularly on the contrast between naturwissenschaft (natural sciences) and geisteswissenschaft (human sciences) (e.g. Dilthey).

The left column is effectively a summary of the current mainstream Anglo-American management canon. The right column is a ‘both…and’ addition to the left. Together they outline my conception of the next management canon. It is not a movement from one canon to a new one but a dynamic synthesis of the old and the new, the conservative and the radical. The dynamic has been described as a dance, but the ‘both…and’ nature of the humanistic perspective, means that it must always embrace and contain the ‘either/or’ scientific view.

In short, the Next Management Canon regards organizations as constantly emerging processes fashioned by humans: creatures of nature, with bodies and intentions, situated in time and space, culture and society, searching for identity and meaning and struggling for credibility and authority.

Life is the ultimate context.

Toggling Between Two Worlds: Making Sense of Organizational Change (abridged)

“And twofold always. May God us keep

From single vision and Newton’s sleep.”

William Blake

This is a summary of a longer article I have just posted on Medium to mark forty years since the publication of my first (and only) article in the Harvard Business Review. That article, Of Boxes, Bubbles and Effective Management, outlined the transformational experience our corporation had been through after it had been acquired in a wildly overleveraged buyout on the eve of a steep recession. We had gone insolvent almost overnight, but owed the bank so much money that it was their problem, not just ours.

I told the detailed story of what had happened, how we had muddled through, dealing with our challenges and what the implications of our eventual survival and success were for management. I approached this task by balancing a then-popular ‘hard’ management model with a ‘soft’ counterpart. This allowed a Taoist ‘yin-yang’ interpretation of our experience. For to me it seemed as if we had switched from a hard, ‘yang’ structure to a softer ‘yin’ process, although not in any unilateral, unconditional way. It had been like a figure-ground reversal with crisis as the catalyst. It was as if the conventional organizational hierarchy had been turned upside down:

The Taoist yin-yang symbol suggests that the ‘yang’ component never went away. Rather, it was held in abeyance for use only in situations that demanded it[1]. Whether you would need it or not all depended on the context.

The Taoist yin-yang symbol suggests that the ‘yang’ component never went away. Rather, it was held in abeyance for use only in situations that demanded it[1]. Whether you would need it or not all depended on the context.

My opening proposition in the article was, “Two models are better than one.” The bottom line after another four decades of experience, reading and research since then is that I don’t think that we can make much headway in management (or politics and the social sciences for that matter) unless we find a way to reconcile science with the humanities in a new synthesis. In the longer article I suggest that an ecological sensemaking framework shows the way ahead.

Why We Need Two Models

In The Witch Doctors: Making Sense of the Management Gurus (1996)[2] John Micklethwait (former editor-in-chief of The Economist, now of Bloomberg News) and Adrian Wooldridge (Former Schumpeter columnist for The Economist, now Bagehot columnist) identified four defects in management theory:

- That it was constitutionally incapable of self-criticism.

- Its terminology confuses rather than educates.

- It rarely rises above common sense.

- It is faddish and bedeviled by contradictions.

After declaring management theory “guilty” on all charges in various degrees, they went on to identify the root cause of the problem as an “intellectual confusion at the heart of management theory; it has become not so much a coherent discipline as a battleground between two radically opposed philosophies. Management theorists usually belong to one of two rival schools. Each of which is inspired by a different philosophy of nature; and management practice has oscillated wildly between these two positions.” They went on to identify the two schools as scientific management on the one hand and humanistic management on the other, concluding that, “This, in essence, is the debate between “hard” and “soft” management.”

We Are the Battleground

It’s time to identify this “intellectual confusion” as a feature of both humans and organizations, not a ‘bug’. It’s time to recognize that our fundamentally divided nature is the essence of our humanity and that it is the practical weaving together of apparently irreconcilable opposites that is the very warp and woof of our existence. The roots of this split are in the need for living creatures to be able, in real time, both to focus on a task at hand and to remain aware of peripheral threats, to live simultaneously in two ‘worlds’[i]. These two tasks must be performed together, yet they demand different kinds of attention and different contexts (the one individual and the other collective). The result is an asymmetrical split-brain architecture that goes a long way down the tree of phylogeny. This suggests that it must have significant survival benefits.

This split, this fundamental duality, spirals through our existence as individuals, families, communities, organizations and societies and throughout our history as a species. It has grown in complexity as our languages, cultures and institutions have grown more complex. Like the twin arms of a double helix it also coils through philosophy in general and the history of management thought in particular. Here the dualities are familiar: exploitation and exploration, calculation and judgement, individual and team, performance and learning, detachment and immersion, mechanical and organic and so on and on.

That’s why we need two models in a Taoist yin-yang relationship to understand organizational change and make sense of our experience.

Reconciliation in Ecology

There will always be a tension between the scientific and the humanistic, but there need not be a battle. We can render the tension creative rather than destructive if we can frame it in a higher-level understanding of the dynamics of life in a real world.

This will mean challenging the assumptions of mainstream Anglo-American management about the nature of reality and what is means to be human. These aren’t ‘wrong’ but have been pushed too far and taken into areas where they don’t belong. They claim to be universal when everything is dependent on context. They appeal to our systemizing mind, while ignoring the empathizing one.[ii] The mainstream doesn’t care. This is where a dual-process theory of cognition and emotion helps with its both…and approach, rather than either/or. It can embrace and contain the mainstream and keep it in its proper place.

This is how we can connect management practice, which is always singular and unique, with theory, which describes the world in terms of rules, generalizations and universals. It is how to approach the debate between ‘relevance’ and ‘rigour’ that has plagued the management academics for so long. It is to handle paradoxes and dilemmas like these that evolution has equipped us with bicameral minds, minds that can focus while still retaining peripheral awareness and ‘toggle’ rapidly between the two modes of perception. In management we can think of it is as instrumental search for truth (to earn a living) conducted within the quest for purpose (to live our lives).

Forty years ago I called the two worlds ‘boxes’ and ‘bubbles’. My recommendation to managers then was that “You have to find the bubble in the box and put the box in the bubble”. That is still good advice.

The table, “A Dual-Process, Ecological View of Management”, expands on this idea by showing some of the key management polarities in a different format: an individual, instrumental search for explanation (right side) conducted within a collective, existential quest for purpose (left side). The central barrier between the left and righthand columns is permeable with infinity loop/adaptive cycle connectors to emphasize the nature of the ‘dancing’ ecological balance between the two that plays out in space and time. At the organizational level the challenge for managers is to toggle between the two modes as the situation demands, keeping the enterprise in the adaptive space, the ‘Goldilocks Zone’, between the extremes.

The journey continues….

[1] People at Gore & Associates call this ‘hierarchy-on-demand’, when the formal hierarchy, instead of being permanent, becomes contingent on the situation.

[2] The Witch Doctors was updated by Adrian Wooldridge in Masters of Management (2011). The major conclusions were unchanged.

[i] McGilchrist, I., (2009), The Master and his Emissary: The Divided Brain and the Making of the Western World, Yale University Press, New Haven, CT.

[ii] Baron-Cohen, S., (2009), “Autism: The Empathizing-Systemizing (E-S) Theory” The Year in Cognitive Science, Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1156: 68-80.

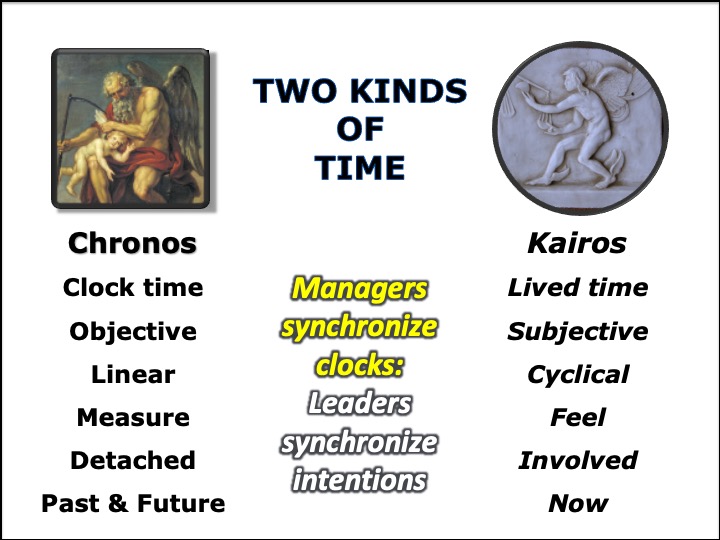

Making Sense of Time: Memory, Attention, Expectation

The ancient Greeks had many concepts of time but believed that two were particularly important. The first was sequential, or chronological, time, the relentless beat of time measured today by watches and calendars. In Greek mythology the personification of time was known as Chronos, familiar to us as Father Time. The abstract, labeled time of past and future—chronos—is captured in our words “chronicle” and “chronometer.” One can also think of it as managerial time, more prosaically as the time of “one damn thing after another,” the linear time of reports and budgets, of histories and forecasts.

The second kind of time for the Greeks was kairos, recalling the youngest of Zeus’s immortal sons. This is the time of seasons, of goals and intentions, of activity and opportunity, which the Romans called occasio. It is the time of now; the infinitely fine-grained, perpetual, thin moment of now in which we all live. The time is always now. Youngest sons always seem to be less encumbered than their older siblings, and, when personified, Kairos is depicted as a young man with wings on his feet and his back that allow him to follow a jinking, butterfly course, crisscrossing Chronos’s linear track. He carries a set of scales in one hand and a knife in the other, ready to cut the thread of time. His head is bald except for a long hank of hair on his forehead. The idea was that if you saw Kairos—opportunity—fluttering toward you, you could seize him by the forelock, but if he got past you, it would be impossible to grab his smooth head from behind.

One can think of kairos as the time of leaders. Effective leaders, in deed and in word, are always pointing out the significance of the moment, the present time, and the opportunities it represents. If the logic of management is all about the maintenance of focus (vertical thinking), then leadership is about the restoration of peripheral vision (horizontal thinking, the ability to make creative connections across fields).

Few have expressed the task better than Mary Parker Follett:

“In business we are always passing from one significant moment to another significant moment, and the leader’s task is pre-eminently to understand the moment of passing . . . it mean[s] far more than meeting the next situation . . . it mean[s] making the next situation.” (Dynamic Administration, emphasis in the original)

Managers meet situations; leaders make them. Managers synchronize watches; leaders synchronize intentions.

Ellen Langer suggests that the ability to situate oneself in the present is the essence of mindfulness, the ability to shake oneself free from the categories of thought derived from the past and to draw novel distinctions. “When we are mindless,” Langer writes, “our behavior is rule and routine governed; when we are mindful, rules and routines may guide our behavior rather than predetermine it.” Being in the present is essential to this. She quotes Saint Augustine, who might be describing the intersection of the two kinds of time: “The present, therefore, has several dimensions . . . the present of things past, the present of things present, and the present of things future.” (Mindfulness)

Today we call them memory, attention, and expectation, but we rarely think of them as aspects of the present.”

The Role of History

From the study of history, managers should feel as if they and their organizations are travelers flowing in a great stream of time, propelled by the past but with many possibilities ahead. Just as is the case when running a real river, one does not succeed by trying to fight the dynamics of the current. One makes progress by using the natural forces in the stream to take one where one wants to go.

The use of history to understand the dynamics of the turbulent stream in this way is well captured in this quote from political scientist Richard Neustadt and historian Ernest May:

“Thinking of time [as a stream] . . . appears . . . to have three components. One is the recognition that the future has no place to come from except from the past, hence the past has predictive value. Another element is recognition that what matters for the future in the present is departures from the past, alterations, changes, which prospectively or actually divert familiar flows from accustomed channels, thus affecting the predictive value and much else besides. A third component is continuous comparison, an almost constant oscillation from present to future to past and back, heedful of prospective changes, concerned to expedite, limit, guide, counter, or accept it as the fruits of such comparison suggest.” (Thinking in Time)

History has predictive value not because the future will be like the past but because some things will continue, habits will endure, and humans will tend to behave in the future much as they have behaved in the past, given similar contexts. Thus, the best use of history is to help sensitize managers to detecting contexts—patterns and changes in patterns—and to hone their contextual intelligence, the practical wisdom and judgment that helps them to anticipate and to adapt. Another name for it is sensemaking.

We cannot predict the future, but we can interpret the past to help us understand the present and anticipate the future. It is the constant oscillation, the constant Janus-like comparison between present and past, present and future that allows effective leaders to continually point out the significance of the moment. It is the moment when chronos and kairos, inevitability and opportunity, come together.

This blog is excerpted from my book, The New Ecology of Leadership: Business Mastery in a Chaotic World, Columbia University Press, New York, NY, 2012. The discussion of Chronos and Kairos is based on Elliott Jaques, The Form of Time.

Keynote Speaking

David Hurst delivers multimedia presentations and a range of customized experiences that will inform and inspire your people and help them learn from the past, master the moment and create the future. For a recent sample of a short keynote to the 10th Annual Global Drucker Forum see the embedded link.

Learn More…

Recent and Book-Related Articles

- The Globe and Mail (2012)

- The Ivey Business Journal

- The European Financial Review (2012)

- Strategy+Business – Why Walmart is Like a Forest (2012)

- Fast Company (2012)

- Plexus Institute

- Practical Wisdom Management Research Review (2013)

- Academy of Management Learning and Education Review

- Plexus Call July 12 Slides and MP3 Audio

- Integral Leadership Review 2013

- Canadian HR Reporter – September 17, 2013

- Faith in Business – Review by Tim Harle Fall 2014

- Post-Rational Management: The Montreal Review – January 2015

- Cultivating Organizations in Leadership & Change May 2015

- The National Post – June 17 2015

- Changing Our Models of Change: The RSA October 21, 2015

- Discovering Complexity: A Story of an Organization in Crisis and Its Response May 2019 Plexus Institute

- Lead Like a Gardener: Agile and Design-thinking will become Fads Unless We Broaden Our Concept of Management (2019)

- True But Useless: Why So Much Management Advice Sucks (and what to do about it) (2020)

Subscribe to David's Blog

The New Ecology of Leadership

A radical retake on the field of management, which stresses creativity, innovation and fair returns for all stakeholders and supplies a mental model and the management tools to do it.

Learn More…

Read a review from the Globe & Mail (PDF)